The Kite that Bridged a River

By M. Robinson

Over a century and a half ago, the mighty Niagara Falls, once

known only to the local Native Americans, was being transformed. Sightseers

packed the banks of the gorge, with their numbers doubling every five years.

Tourism was exploding upon this natural wonder. In 1845, railroad

advertisements, calling it “The center of a vortex of travel”, both

cheapened and glamorized it. The promoters of two major railroad lines,

Canada’s Great Western and New York’s Rochester and

Niagara, the forerunner of New York Central, touted

Niagara Falls as the new tourism Mecca. The majestic sight of Niagara Falls,

previously visited and viewed only by the fortunate privileged class, was

becoming more available to the general public.

Over a century and a half ago, the mighty Niagara Falls, once

known only to the local Native Americans, was being transformed. Sightseers

packed the banks of the gorge, with their numbers doubling every five years.

Tourism was exploding upon this natural wonder. In 1845, railroad

advertisements, calling it “The center of a vortex of travel”, both

cheapened and glamorized it. The promoters of two major railroad lines,

Canada’s Great Western and New York’s Rochester and

Niagara, the forerunner of New York Central, touted

Niagara Falls as the new tourism Mecca. The majestic sight of Niagara Falls,

previously visited and viewed only by the fortunate privileged class, was

becoming more available to the general public.

A bridge spanning the turbulent gorge was envisioned. It would provide a highway over the gorge and allow commerce and people to pass more freely between Canada and the United States. Charters were obtained in 1846 from the Government of Upper Canada and the State of New York for the formation of two companies that were to own the bridge jointly; the Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge Company in Canada, and the International Bridge Company the USA. There must have been dollar signs dancing in their eyes as they calculated that the number of tourists would double as soon as the bridge was passable. Even at a toll of 25 cents per passenger, they felt that the bridge would be profitable within the first year alone. Up until this time, the only way to cross the imposing gorge was to go upstream and take a turbulent ride in a small ferry. The joint commission knew very little about bridge building. They did not even know if spanning a gorge 800 feet wide and 200 feet deep was practical. The leading engineers of Europe and North America were polled and quickly gave a negative response and opinion of the projects viability.

There were only four men who said it could be done; that building a bridge across the tumultuous Niagara River was possible. An interesting detail in this story is that all four of these men (Ellet, Roebling, Keefer, & Serrell), would each eventually build a suspension bridge across the Niagara Gorge somewhere between Niagara Falls and Lewistown; a distance of about 15 miles, all within a few years of the original Request For Information.

On November 9, 1847 after quite a contentious competition, an

Engineer, described as swift and impetuous, Charles Ellet Jr. of

Philadelphia, was awarded the contract to construct a bridge at the chosen

site. Ellet, also known to be flamboyant, bold and ambitious, was extremely

anxious to be the first man to bridge the Niagara River. This had been his

burning desire since 1833 when he believed the Niagara offered him the

greatest challenge. After studying suspension bridges in France, Ellet is

quoted as saying, about the bridge across the natural chasm, that he did not

know “…in the whole circle of professional schemes, a single project which

it would gratify me so much to conduct it to completion.”

On November 9, 1847 after quite a contentious competition, an

Engineer, described as swift and impetuous, Charles Ellet Jr. of

Philadelphia, was awarded the contract to construct a bridge at the chosen

site. Ellet, also known to be flamboyant, bold and ambitious, was extremely

anxious to be the first man to bridge the Niagara River. This had been his

burning desire since 1833 when he believed the Niagara offered him the

greatest challenge. After studying suspension bridges in France, Ellet is

quoted as saying, about the bridge across the natural chasm, that he did not

know “…in the whole circle of professional schemes, a single project which

it would gratify me so much to conduct it to completion.”

The location of the chosen site was at the narrowest point of the gorge, immediately above the Whirlpool Rapids. The bridge was to connect the site of what was to become the Canadian village of Elgin (later Clifton, and then Niagara Falls, Ontario), with the American Village of Bellvue (now Niagara Falls, NY).

Ellet was about to begin construction in January of 1848 when he was faced with his first obstacle. The building of a suspension bridge is commenced with the stretching a line or wire across the stream. However, it was the turbulent roaring rapids, the 800-foot wide gap, and the 225-foot high shear cliffs of the Whirlpool Gorge that made a direct crossing impossible. Ellet and his colleagues, to ponder this dilemma, held a dinner meeting at the Eagle Hotel in the Village of Niagara Falls, New York. The conversation revolved around various methods to get the first line across the Gorge. Ellet, himself, proposed the use of a rocket. A bombshell hurled by a cannon was suggested. Some thought a steamer might navigate the rapids, knowing that the Whirlpool Rapids would devour any smaller craft and that ferries were too far upstream.

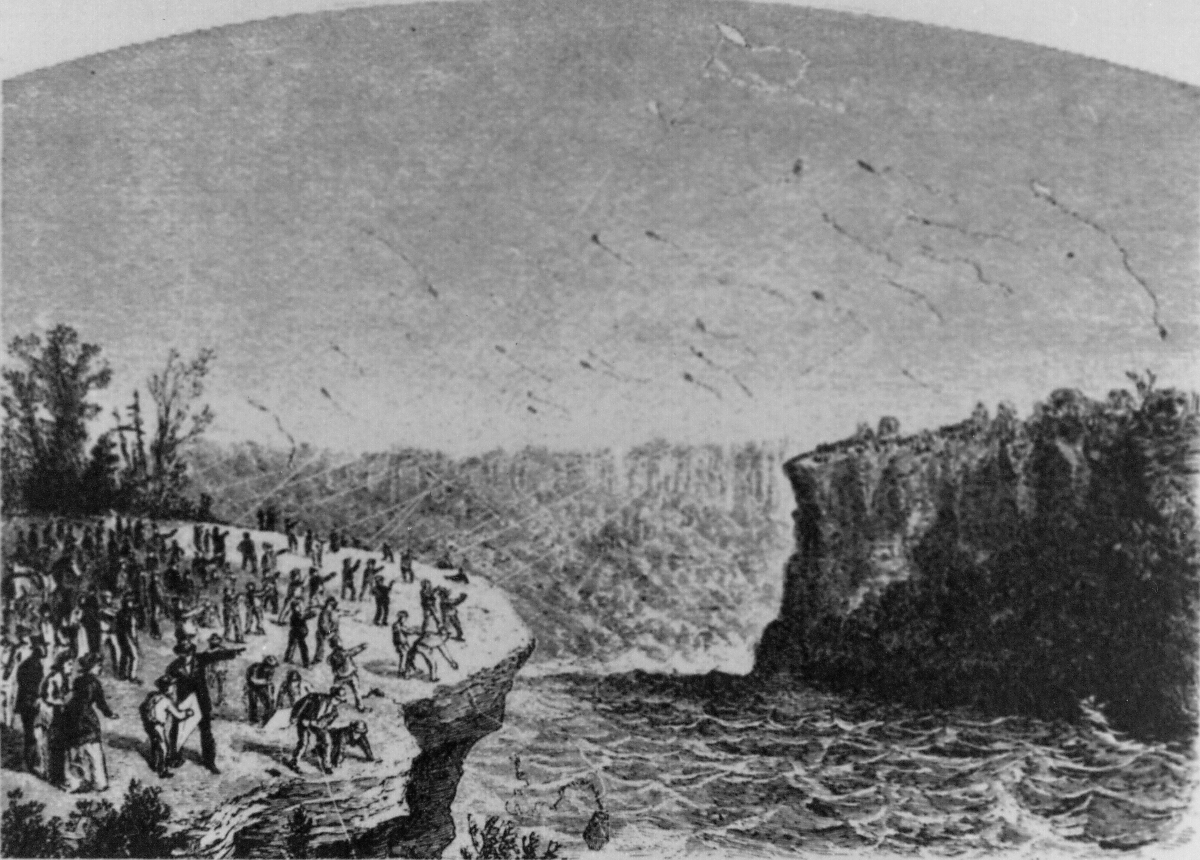

Local ironworker, Theodore G. Hulett (future Judge), suggested offering a cash prize to the first boy who can fly his kite to the opposite bank. The promotional prone bridge builder probably enjoyed exercising originality, and invited the areas youngsters to a kite-flying contest.

There was a tremendous turn out for the kite contest that was held in January of 1848. The kites began appearing on the Canadian side of the gorge, taking advantage of prevailing winds from West to East. The first to succeed in spanning the gorge with his kite, named the ‘Union’, was fifteen-year-old American, Homan Walsh. Homan crossed to the Canadian side of the gorge by ferry just below Niagara Falls, and walked the two miles along the top of the cliff to the location that the bridge was to be built. Homan had to wait a day for the wind to cooperate; it was a kite contest after all! However, on the second day, the winds were perfect and Homan’s kite went right up and flew high above the gorge.

Homan’s kite flew all day and into the night. At midnight, as

he had expected, the wind died and the kite began to descend. Then there was

a sudden pull of the line, and it went limp. He realized what happened.

Homan’s kite string had broken. It was cut on the edge of the sharp rocks

and broken ice. The bad luck continued for Homan Walsh, the ferry wasn’t

crossing the river because the broken ice made it too dangerous. He was

marooned on the Canadian side in the town of Clifton for eight days.

Fortunately he stayed with friends while he waited for the ice to clear

enough to resume ferry service.

Homan’s kite flew all day and into the night. At midnight, as

he had expected, the wind died and the kite began to descend. Then there was

a sudden pull of the line, and it went limp. He realized what happened.

Homan’s kite string had broken. It was cut on the edge of the sharp rocks

and broken ice. The bad luck continued for Homan Walsh, the ferry wasn’t

crossing the river because the broken ice made it too dangerous. He was

marooned on the Canadian side in the town of Clifton for eight days.

Fortunately he stayed with friends while he waited for the ice to clear

enough to resume ferry service.

Finally, after eight days, he was able to go back to the US side, retrieve his kite, and repair it. Homan Walsh then made his way back to the Canadian cliff side, where he was able to fly the kite to the opposite bank. There it was caught and attached to a tree. He won the kite-flying contest on (or about) January 30, 1848, and was awarded the cash prize. His cash prize was either five or ten dollars (US). Accounts vary, depending on publications.

Why the kite contest, and commencement of construction, was started in the dead of winter, is difficult to comprehend, given the severity of the weather. In fact, the only reference found to weather was the listing of the ice jam that kept Homan Walsh on the Canadian side for eight days, and later as a cause of a construction accident.

Eighty years later, Homan Walsh, then living in Lincoln, Nebraska, recounted that his most precious memory was this exploit of his boyhood – his part in starting the first bridge over the gorge.

The day following the successful kite flight, a stronger line was attached to the kite string. A rope followed, and eventually a cable consisting of thirty-six strands of number 10 wire.

On January 31, 1848 the Buffalo Dailey Courier

published this account; “We have this day joined the United States and

Canada with a cord, half an inch in diameter, and are making preparations to

extend a foot bridge across by the first of June. Our Shanties are erected

and we have a large number of men at work. Everything is going ahead. Men

are very busy laying out the town of Bellevue, and are making arrangements

for putting up a large hotel. The situation is a beautiful one, and bids

fair, in the opinion of many to surpass the town at the Falls. I will keep

you advised of the progress.”

On January 31, 1848 the Buffalo Dailey Courier

published this account; “We have this day joined the United States and

Canada with a cord, half an inch in diameter, and are making preparations to

extend a foot bridge across by the first of June. Our Shanties are erected

and we have a large number of men at work. Everything is going ahead. Men

are very busy laying out the town of Bellevue, and are making arrangements

for putting up a large hotel. The situation is a beautiful one, and bids

fair, in the opinion of many to surpass the town at the Falls. I will keep

you advised of the progress.”

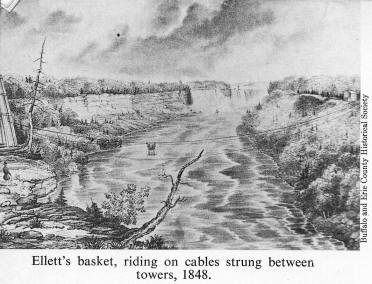

Ellet then built two temporary, fifty-foot wooden towers facing each other across the gorge. There was 1,200-foot of cable that passed over and was anchored to the towers. The next challenge faced by Ellet and his bridge building team was how to get the materials, supplies, and workman shuttled back and forth across the gorge.

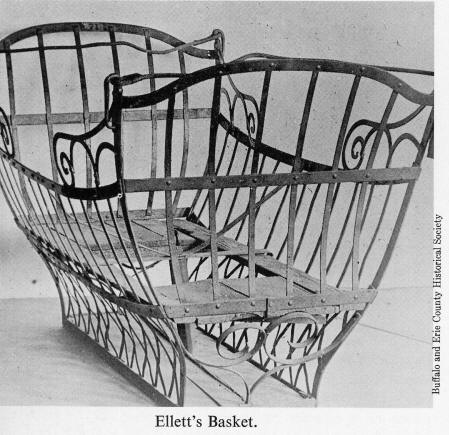

It was time for another meeting in the Eagle Hotel Tavern. Over pints of ale, Ellet and Hulett designed an iron basket. The completed basket looked like two high backed rocking chairs facing each other. The iron basket would hang suspended from rollers on the cable and be winched from one side to the other by a man turning a windlass.

Ellet, always in search of publicity, decided he would be the one to make the maiden voyage across gorge in the precarious cable car, going from one side and then to the other. On March 13, 1848 he wrote to the bridge companies:

“Dear Sirs, I raised my first little wire cable on Saturday, and anchored it securely both in Canada and New York. Today (Monday) I tightened it up, and suspended below it an iron basket which I had caused to be prepared for this purpose, and which is attracted by pulleys playing along the top of the cable. In this little machine I crossed over to Canada, exchanging salutations with our friends there, and returned again, all in fifteen minutes. The wind was high and the weather cold, but yet the trip was a very interesting one to me - perched up as I was two hundred and forty feet above the rapids, and viewing from the centre of the river one of the sublimest prospects which nature has prepared on this globe of ours. My little machine did not work as smoothly as I wished, but in the course of this week I will have it so adjusted that anybody may cross in safety.”

It wasn’t long before others were lining up to pay a fee and go for a ride across the gorge. It quickly became the most novel thrill of the Niagara. Ellet’s contract did not allow for him to collect tolls… so he didn’t. He charged $1.25 to “Observe first hand the engineering wonder of bridging the Niagara”. Often up to 125 people a day crossed the gorge, three-quarters of them woman. One man, so the story goes, took one look at Ellet’s iron basket and opted for the little rowboat passing as a ferry. Then he walked the two miles back to the bridge site to meet his wife, who was calmly getting out of the iron basket. Ellet’s original iron basket is currently on display in the collection of The Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society in Buffalo, NY.

Ellet completed his service bridge in July 1848. Going from

bank to bank in a horse drawn carriage must have been astonishing. Charles

Ellet Jr. was so impatient that he didn’t wait for the safety railings to be

constructed on both sides of the span. He called for a horse and buggy, and

standing with the reins in his hands, “Like a Roman Charioteer”, one

newspaper reported, drove himself across the flimsy structure to the cheers

of the spectators. The report also stated that women fainted at the sight

and strong men gasped. But, as author Pierre Berton noted, “Women were

forever fainting and strong men gasping in the records of that century.”

Ellet completed his service bridge in July 1848. Going from

bank to bank in a horse drawn carriage must have been astonishing. Charles

Ellet Jr. was so impatient that he didn’t wait for the safety railings to be

constructed on both sides of the span. He called for a horse and buggy, and

standing with the reins in his hands, “Like a Roman Charioteer”, one

newspaper reported, drove himself across the flimsy structure to the cheers

of the spectators. The report also stated that women fainted at the sight

and strong men gasped. But, as author Pierre Berton noted, “Women were

forever fainting and strong men gasping in the records of that century.”

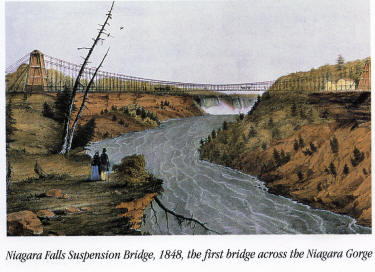

The bridge that was built with the aid of a kite was officially opened to the public in August 1, 1848. As bridges went, Ellet’s was somewhat primitive. It was 762 feet long and 8 feet wide. It was a heavy oak plank roadway suspended 220 feet above the river from iron cables, elevated on either side. It seemed originally intended more as a novelty for tourist or as a convenience for local residents, than as a commercial highway.

Seven years later, however, using Ellet’s span as scaffold, a railroad suspension bridge across the Niagara was completed. To carry the traffic loads of the day, a suspension bridge of two levels was proposed. The lower deck would be for horse drawn carriages and pedestrians, and the upper deck for train traffic. They said it couldn’t be done, but an Engineer, John Roebling, had a secret technique. The secret was an invention he devised for the manufacture and winding of steel wire into cables. If he could only get them to let him try it! They did, he did, and on March 8, 1855, the steam engine London, weighing 23 tons, crossed the new double-decked bridge at a brisk speed of 8 miles an hour.

All because of a kite!

Another bit of kiting trivia from Niagara Falls

Newspaper Accounts:

Buffalo Commercial Advertiser and Journal, Monday, January 31, 1948 (citing Iris of Niagara) – Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge

Buffalo Dailey Courier, Thursday, February 3, 1848 – Niagara Suspension Bridge

Niagara Chronicle, Friday, February 4, 1848 (citing Manchester NY Iris) – Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge

Buffalo Morning Express, Thursday, February 10, 1848 (citing Lockport Courier)

Buffalo Dailey Courier, Saturday, July 29, 1848 – The Suspension Bridge, Completion of the Foot-Way

Buffalo Commercial Advertiser and Journal, Monday, July 31, 1948

Buffalo Dailey Republic, Friday, August 25, 1848 (citing Iris of Niagara) – Suspension Bridge

Niagara Falls Gazette, Thursday, January 27, 1938 – A Peep Into The Past, by Old Timer

Magazine Articles:

Scientific American,

Vol. 2, Issue 14, December 26, 1846 – Niagara Suspension Bridge

American Kite Magazine, Summer 1991, Vol. 4, No. 2 – The Great Kite Contest, by Tom Allan

Niagara Falls Centennial International Kite Festival (pamphlet), Spring 1992 – So Who Is Homan Walsh?, By Bill Albers

Books and References:

Niagara, A History of The Falls (1992), by Pierre Berton

Niagara Falls, Canada – A History (1967), Kiwanis Club, Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada

Niagara Falls – A Pictorial Journey (1998), by Margaret Dunn

Charles Ellet, Jr., The Engineer as Individualist (1810-1862), by Gene D. Lewis

Niagara – River of Fame (1986)

Spanning Niagara – The International Bridges 1848 – 1962

The Niagara – Across the River, One Way or Another

Many thanks to my research staff (Bill Albers) for his inquisitive mind and his dedication.

Written, in Celebration, precisely on the 157th Anniversary of the Kite Event

© 2005 M Robinson