The

article below is a reprint of a piece that was written (Author Unknown) and

published in December of 1909, six years after the Wright brothers’ historic

flight. It was most recently published in SEE THEM FLYING: Houston

Peterson’s Air-Age Scrapbook 1909-1910.

The

article below is a reprint of a piece that was written (Author Unknown) and

published in December of 1909, six years after the Wright brothers’ historic

flight. It was most recently published in SEE THEM FLYING: Houston

Peterson’s Air-Age Scrapbook 1909-1910.

Thanks to M. Robinson for the copy.

THE REAL STORY OF HOW MEN LEARNED TO FLY

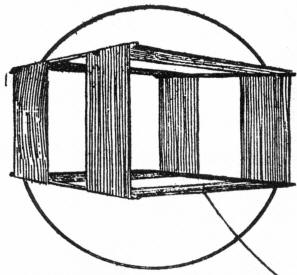

The kite is really the father of the flying machine. A kite with a gas engine aboard is, in fact, what has solved the problem.

I t

was the hope of taking a ride in a big cloth kite—a hope which many a boy

has cherished in his heart—that set the Wright bothers to experimenting with

what became, seven years later, the first successful flying machine.

t

was the hope of taking a ride in a big cloth kite—a hope which many a boy

has cherished in his heart—that set the Wright bothers to experimenting with

what became, seven years later, the first successful flying machine.

"Let’s build a kite strong and light enough and with enough surface to lift a man," said Orville to Wilbur.

"About 500 square feet of surface ought to be enough to lift a man. Anyway we can soon find out by trying how big the kite should be."

"We will make the kite something like a Hargreave box kite, with top and bottom surfaces. Then I will get in between, and you take the rope and run with the kite."

This was the plan as proposed by the younger brother. Wilbur said: "Bully. We’ll try it."

"But where," both asked, simultaneously, "can we play with a big 40 foot kite without attracting a crowd and making ourselves look silly?"

This looked like a staggerer. A couple of bicyclemakers in Dayton running up and down the streets flying a 40 foot kite would have disturbed trade, to say the least. And a crowd of hooting boys would be in the way.

WILBUR’S IDEA

But Wilbur had an idea.

"Suppose," he said, "we go to some lonesome, godforsaken piece of the seashore. The wind will be steady, and that’s one very important thing: the more lonesome it is the cheaper will be the living. We can knock up an inexpensive shed and this will serve for shelter for us and as a workshop and shelter for the kite. Why not?"

So the brothers wrote to the weather bureau at Washington, and asked about wind currents, and where they could find a steady, strong wind.

FOUND THE PLACE

The weather bureau is full of information of this sort, and came back with a reply saying that the Cape Hatteras section of the Carolina coast had 20 mile winds almost all the time. The government maintained an observation station at Manteo, an island near the life saving station at Kitty Hawk, near Kill Devil Hill. The place was quite remote, but provisions could always be had at Manteo.

The letter of the weather bureau man added that there were great sand hills—drifted by the wind—on the spit where the life saving station stands—hills four and five hundred feet high.

"Great," said Orville. "We could fly the kite from the top of one of the sand hills."

So the Wright brothers worked in their shop in Dayton, making the parts of a big kite, which was carefully designed on paper. Then they bought and shipped some rough lumber and tools to Manteo, together with parts of their kite, and with gay hearts set out for a novel summer outing. For the Wrights at this time (1898) did not admit to themselves that they were doing anything but amusing themselves—playing in their own way.

GREAT SPORT

It

was good sport. They built their shed, put together the parts of their kite,

and flew it. There was plenty of wind, plenty of room, and nobody to look on

or laugh except a lonesome coast guard.

It

was good sport. They built their shed, put together the parts of their kite,

and flew it. There was plenty of wind, plenty of room, and nobody to look on

or laugh except a lonesome coast guard.

The kite flew, and it was strong enough to carry up Orville, when he lay "belly-whopper" between the upper and lower planes of the kite. That part of the theory was all right. But the kite would not stay up with its human freight. The wind was not strong enough to keep running with the rope.

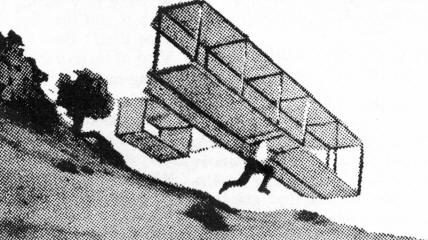

But they found a new game. They found the kite to be fine for "sliding down hill on the air". Instead of using a rope to fly it they took the kite to the top of a sand hill and sent it off into the teeth of the wind. All that was needed was a slight upward tilt of the planes and the wind would almost support the weight of man and planes. It would, in fact, support the thing long enough to make a long glide from the top of the hill to a point eight or ten hundred feet from the starting point.

FINE GLIDING

This was "gliding". The kite became a "gliding" machine. The man aboard kept the thing balanced by wiggling his body, and sometimes the glider would be able to hover in the air like a soaring bird for almost a minute, supported merely by keeping the surfaces tilted up against the wind.

The kite "stays up" (that is, overcomes the downward pull of gravity), because it is tilted upwards against a moving stream of air. The gliding machine—which is simply a kite without a string—is supported in the same way.

All this was soon clear to the Wrights. They found that a couple of surfaces 40 by 60 feet, built of strong, light wood and covered with stout cloth, were enough to support the weight of a man, if those surfaces were kept slightly tilted against a continuous volume of wind blowing at 35 or 40 miles an hour. Less would not be enough to maintain the weight.

The next important problem was to keep the apparatus balanced and to steer it. Without some steering apparatus it was hard to keep the planes tilted upward at the proper angle, and it was hard to keep the machine on a straight course.

WORKED LONG TIME

So the Wrights spent several summers working on these problems. They fixed up a small plane in front that could be moved up and down. That gave the tilt. Move the small plane up and the machine would climb; move it down and it would head towards the ground.

With these attachments gliding became a science. It was no trick at all to start from the top of Kill Devil Hill and go sailing off towards the ocean, remaining in the air for several minutes.

"If she only had something to keep her going", then said Wilbur, "instead of going a quarter of a mile she would go as many miles as we might want."

"That would be a real flying machine, wouldn’t it?" assented Orville.

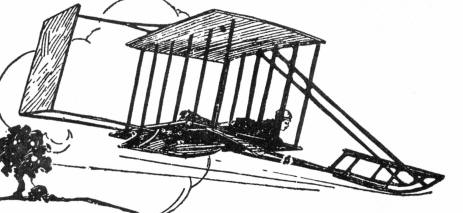

"A couple of propellers," continued Wilbur. "Driven by a light gasoline engine ought to be able to drive her through the air fast enough to keep her afloat."

"Let’s try," said Orville.

So

they set to work (in 1900) figuring out the weight of a motor and

propellers, and the size of a glider, which would lift the weight of the

motor in addition to a man.

So

they set to work (in 1900) figuring out the weight of a motor and

propellers, and the size of a glider, which would lift the weight of the

motor in addition to a man.

In the fall of 1903 the brothers were at Kitty Hawk hard at work putting together the parts of a glider with a gasoline engine driving two large propellers, similar to those which drive a ship in the water. The cold weather was coming on, but the young men worked on through September, October, November and even into December, with no shelter but their barn and only an oil stove to warm them.

SUCCESS AT LAST

At last (Dec. 17, 1903) everything was ready for a try. The motor sparked, the propellers whizzed, the engine roared. Orville crawled into his place in the machine. Wilbur balanced it along the monorail. She was off; in the face of a wind blowing 25 miles an hour the machines crept forward. She rose gently from the ground; she skimmed along, free of all support, about 10 feet from earth, and after covering between 800 and 900 feet, came back to earth.

Man has learned to fly.

That performance at Kitty Hawk was the first flight of man in a heavier-than-air machine.

The work of the Wrights since then has been devoted to finding ways to get better control over the planes.

PHOTO CAPTIONS

7A ~ FIRST STAGE, THE HARGREAVE KITE.

7B ~ SECOND STAGE, WILBUR WRIGHT OPERATING THE "GLIDER" AT KITTY HAWK.

7C ~ THIRD STAGE, SHOWS TRANSFORMATION OF THE "GLIDER" INTO AN AEROPLANE AT KITTY HAWK.