The Flying Cowboy

By M

Robinson

Samuel Franklin Cody had to be

one of the most colorful and entertaining aviation pioneers. He was born in

Birdville, Texas in 1861 into the prairie life of a cowboy. His boyhood is pure

American Wild West; catching and training wild horses, becoming a highly skilled

buffalo hunter, rifle and lasso expert, and gold prospector in the Yukon.

Samuel Franklin Cody had to be

one of the most colorful and entertaining aviation pioneers. He was born in

Birdville, Texas in 1861 into the prairie life of a cowboy. His boyhood is pure

American Wild West; catching and training wild horses, becoming a highly skilled

buffalo hunter, rifle and lasso expert, and gold prospector in the Yukon.

After touring America for a few

years in a Wild West show billed as ‘Captain Cody, King of the Cowboys’

he decided to settle in England in 1890 eventually becoming a naturalized

English citizen.

Cody became a showman and

drafted his immediate family into forming a touring company. During these shows

Cody’s considerable skill in riding, lassoing, and shooting were demonstrated in

music halls. His persona of extravagant dress was adopted from his friend ‘Buffalo

Bill’. In addition to the shoulder length hair, beard, mustache, Stetson,

fringed buckskins and cowboy boots, there was a close physical resemblance that

helped Cody to purposely blur the line between himself and Buffalo Bill.

In 1898 Cody produced a show

called The Klondyke Nugget that was based on his life during the gold

prospecting years in the Yukon. The gory melodrama was a huge financial success

as it highlighted the individual talents of the various Cody’s.

Leon Cody, (Samuel’s son) had

become very interested as well as proficient in kite flying and during this time

the father and son team began competing with kites that became increasingly

larger in size. Cody himself was said to have learned about kites from a Chinese

cook back on the Cody ranch in Texas.

By 1900 the tides had turned and

Cody’s passion for his hobby of kiteflying had surpassed his previous interests

of show business. Fortunately the Klondyke Nugget continued to play to packed

houses and enabled him financially to experiment with a series of kite

configurations. This was apparently very necessary since there was a newspaper

account reporting that his first manned air flight using kites in tandem lifted

him eighty feet in the air when all of a sudden a gust of wind made the kites

dive into some trees. Cody’s ability to hang onto the upper branches of the tree

is said to have saved his life. He vowed at this time to redesign the kites.

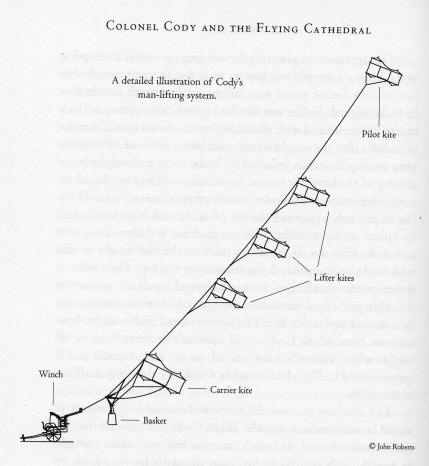

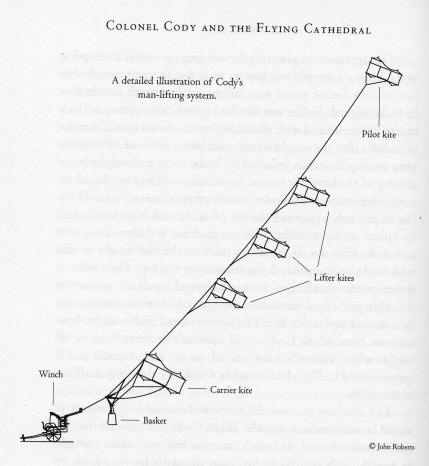

Cody did extensive research on a

variety of designs and eventually decided that his ‘bat’ design was the

way to go. The bats, as they were called were double celled Hargrave box kites

with wings added for additional lift, scalloped edges on the wings for

stability, and a topsail, which he patented in 1901. With this kite Cody

developed an amazing man-lifting system.

Cody’s man-lifting system

started with a small steadying pilot kite, then was followed by a team of lifter

kites, with the number of lifter kites depending on the wind conditions. These

lifter kites were attached to the main flying cable by two towing rings, one at

the head of the kite, and one at the towing point of a four legged bridle. When

released, the kite would go up the flying line, which had a number of cone

shaped stops at predetermined points along the flying line. The conical stops

became progressively larger as they approached the top of the line,

corresponding to the increasing size of the tow rings. So, as the first lifter

kite traveled up the line, its large towing ring would pass over the smaller

cones stopping its free travel as it reached its predetermined mooring point.

Then the next lifter kite would be released with a little smaller towing ring

until it stopped against the next to last one. After a satisfactory number of

lifter kites were secured to the cable, the carrier kite was attached to a

trolley, the wheels of which ran along the top of the cable. From this trolley

was suspended the wicker basket that carried the passenger aloft. The carrier

kite was released and it traveled up the cable towards the lower lifter kite.

The brave passenger could control the ascent and descent by working a

complicated system of lines and brakes. The lines gave the kite greater or

lesser lift by adjusting the inclination of the kite to the horizontal.

Cody was so thrilled with his

invention that he demonstrated it for the British military. It was proposed that

in military applications the passenger could be outfitted with a; telescope,

telephone, camera, and firearm and lifted to an altitude of 3,500 feet.

The British military authority

was not at all interested Cody’s initial approaches.

It has been said that in spite

of Cody’s ornate fashion sense, and his claim to be illiterate, he was a man of

a great deal of intelligence. He had an extremely practical outlook that was

bolstered by what seemed to be incredible amount of courage, strength and

determination.

Even with all this going for

him, the first impression that Cody presented to people made them reluctant to

take his aeronautical career very seriously. Initially his considerable

achievements in the air…considered by some to be the maker of the first

practical flying machine… were perceived to be merely an extension of his

show-business promotion.

However the British military

authorities were so impressed with his ability as a marksman they offered him a

position as a shooting instructor at Aldershot. Cody declined the offer.

Cody was undaunted. His

perseverance to his kite plans were firmly intact, so Samuel Franklin Cody did

what he did best…promote himself and his interest with passion.

To publicize the traction

potential of his system Cody successfully crossed the English Channel using a

collapsible boat powered by kites, it was November of 1903 and it took thirteen

hours. Cody’s boat was a modification of a collapsible dinghy that was 13 feet

long, a deck covered with cork for maximum buoyancy, and a well ballasted keel.

In order to keep the line taut, a drogue anchor was towed behind the boat to

provide resistance to the pull of kites. Prior to this successful trip which was

made from Calais to Dover, several un-successful attempts were made from Dover,

all of which were met with adverse wind conditions.

To publicize the traction

potential of his system Cody successfully crossed the English Channel using a

collapsible boat powered by kites, it was November of 1903 and it took thirteen

hours. Cody’s boat was a modification of a collapsible dinghy that was 13 feet

long, a deck covered with cork for maximum buoyancy, and a well ballasted keel.

In order to keep the line taut, a drogue anchor was towed behind the boat to

provide resistance to the pull of kites. Prior to this successful trip which was

made from Calais to Dover, several un-successful attempts were made from Dover,

all of which were met with adverse wind conditions.

These crossings resulted in many

public demonstrations of the invention and created positive publicity. During

this time Mrs. Cody also flew in her husbands man carrying kites to show her

confidence in his invention. All this had the desired effect and the military

finally became interested in his work with kites.

These crossings resulted in many

public demonstrations of the invention and created positive publicity. During

this time Mrs. Cody also flew in her husbands man carrying kites to show her

confidence in his invention. All this had the desired effect and the military

finally became interested in his work with kites.

The British Admiralty Commission

invited Cody to demonstrate his man hauling kites on Whale Island in Portsmouth

at the end of 1903. The first one to go up was Cody’s son Vivian who went up two

hundred feet to take photographs. He was followed by Cody himself who went up

for hundred feet. Then Leon went up eight hundred feet on a kite and took photos

of the warships in the harbor.

It has been said that for all

intents and purposes this was the birth of the Royal Air Force.

Despite the war offices initial

reluctance to associate with Cody, the following year he was engaged by the war

office to experiment with kites for artillery observation and photo

reconnaissance. The Admiralty put warships at Cody’s disposal and extensive kite

trials were carried out on both land and water during 1904 and 1905. What could

certainly be a record height of 2,600 feet ( 792.6 m ) was attained during these

trials on cable that was 4000 feet ( 1219 m ) long.

At long last, the War Office

adopted Cody’s system in 1906 for Army observation. It was then, that S.F. Cody

was given what was perhaps the first official ‘title’ in Western Kite

History. Cody was granted Officer status with the post of Chief Kite

Instructor to the British Army at Farnborough, where his duties included the

design and manufacture of kites, as well as giving instruction in the operation

of these contraptions. The salary Cody received for this position was one

thousand pounds annually plus free fodder for his (now famous) white stallion,

commonly known to be his favorite mode of transportation.

During the very early 1900’s

there were numerous kite competitions held throughout Europe with the most

prestigious being organized by the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain. It was

common to see Cody, his son Leon, and Baden-Powell, among others, frequently

listed on the competitors list. In June of 1903 Cody took second place in the

International Kite Trials at Worthing Down which earned him membership in the

Aeronautical Society, later becoming the Royal Aeronautical Society.

Just as Cody’s persona was large

and memorable, so too was his influence. His talent at promotion brought

aeronautical pioneers and their experiments to the forefront by continually

making news. One of the consequences of Cody’s experiments was the 1909

competition held by Charles Dollfus of France, to locate for the French Military

Authorities the most successful man-lifting technique available. Using a system

very similar to Cody’s, Captain Madiot won first prize, although he later died

during a flying accident before his project could be brought to fruition. In the

aftermath the French army chose Captain Saconney’s system, which also bore a

resemblance to Cody’s original set up.

Kites for use by the military

were not the only direction Cody took with his kites.

Cody was made a Fellow of the

Royal Meteorological Society for his contribution to weather research. On one

particular occasion Cody lifted instruments to the (then) record altitude of

14,000 feet ( 4,268m ). Cody gave a demonstration of a modern day weather

instrument called the meteorograph that had been developed by the

Meteorological Office to register: height, temperature, humidity, and wind

velocity, during a kite display at Cobham Common in 1907.

Cody’s curiosity, courage and

enthusiasm inevitably led him to experiment with powered flight, and in October

of 1908 he became the first man to build and fly an aeroplane in Britain. Five

years later on August 7, 1913 Cody and his passenger were killed when flying in

Cody’s most recent development the Waterplane.

As described in the Cody

Biography Colonel Cody and the Flying Cathedral by Garry Jenkins…

“In October 1908 Cody had

been the first man to fly in Britain. In the five adventure filled years that

followed he had become what Vanity Fair magazine called ‘The British public’s

chief and best showman of flight’… On August 11, 1913 the British Army’s

headquarters at Aldershot witnessed a scene unprecedented even in its long and

valorous history…By early afternoon, according to the most reliable reckonings,

100,00 people had positioned themselves along the aspen lined lanes, from the

village of Ash Vale in Surrey to the Military Cemetery at Thorn Hill three miles

away…The procession was the largest the home of the British Military

establishment had ever seen…with the crowds standing two and three deep in many

places…His death had provoked an outpouring of spontaneous grief. ‘Millions who

had never seen him felt they had suffered a loss, almost as if they had lost a

friend’ wrote one who had known him…King George V had been among those to

express their grief …The King’s message captured the public mood, and added new

momentum to the campaign for Cody to be buried with full military honors. In the

immediate aftermath of his death, his family had begun arrangements for a small,

private funeral and internment at a local church. Within forty-eight hours,

General Haig and the War Office had offered Cody a plot within Thorn Hill, a

site ordinarily reserved for officers and holders of the military’s highest

honor. As far as anyone could ascertain, he was the first civilian to be granted

such an honor. He was certainly the first Wild West cowboy to be laid alongside

the heroes of Britain’s glorious military past.”

“In October 1908 Cody had

been the first man to fly in Britain. In the five adventure filled years that

followed he had become what Vanity Fair magazine called ‘The British public’s

chief and best showman of flight’… On August 11, 1913 the British Army’s

headquarters at Aldershot witnessed a scene unprecedented even in its long and

valorous history…By early afternoon, according to the most reliable reckonings,

100,00 people had positioned themselves along the aspen lined lanes, from the

village of Ash Vale in Surrey to the Military Cemetery at Thorn Hill three miles

away…The procession was the largest the home of the British Military

establishment had ever seen…with the crowds standing two and three deep in many

places…His death had provoked an outpouring of spontaneous grief. ‘Millions who

had never seen him felt they had suffered a loss, almost as if they had lost a

friend’ wrote one who had known him…King George V had been among those to

express their grief …The King’s message captured the public mood, and added new

momentum to the campaign for Cody to be buried with full military honors. In the

immediate aftermath of his death, his family had begun arrangements for a small,

private funeral and internment at a local church. Within forty-eight hours,

General Haig and the War Office had offered Cody a plot within Thorn Hill, a

site ordinarily reserved for officers and holders of the military’s highest

honor. As far as anyone could ascertain, he was the first civilian to be granted

such an honor. He was certainly the first Wild West cowboy to be laid alongside

the heroes of Britain’s glorious military past.”

© M. Robinson, 2003

References:

Books

World on a String the Story of Kites by Jane Yolen

Colonel Cody and the Flying Cathedral by Garry Jenkins

The Penguin Book of Kites by David Pelham

Kites; an historical survey by Clive Hart

The Complete Book of Kites and Kite Flying by Will Yolen

Catalogs

The S. F. Cody Archive by Sotheby’s

Internet

www.Drachen.org

Samuel Franklin Cody had to be

one of the most colorful and entertaining aviation pioneers. He was born in

Birdville, Texas in 1861 into the prairie life of a cowboy. His boyhood is pure

American Wild West; catching and training wild horses, becoming a highly skilled

buffalo hunter, rifle and lasso expert, and gold prospector in the Yukon.

Samuel Franklin Cody had to be

one of the most colorful and entertaining aviation pioneers. He was born in

Birdville, Texas in 1861 into the prairie life of a cowboy. His boyhood is pure

American Wild West; catching and training wild horses, becoming a highly skilled

buffalo hunter, rifle and lasso expert, and gold prospector in the Yukon.

To publicize the traction

potential of his system Cody successfully crossed the English Channel using a

collapsible boat powered by kites, it was November of 1903 and it took thirteen

hours. Cody’s boat was a modification of a collapsible dinghy that was 13 feet

long, a deck covered with cork for maximum buoyancy, and a well ballasted keel.

In order to keep the line taut, a drogue anchor was towed behind the boat to

provide resistance to the pull of kites. Prior to this successful trip which was

made from Calais to Dover, several un-successful attempts were made from Dover,

all of which were met with adverse wind conditions.

To publicize the traction

potential of his system Cody successfully crossed the English Channel using a

collapsible boat powered by kites, it was November of 1903 and it took thirteen

hours. Cody’s boat was a modification of a collapsible dinghy that was 13 feet

long, a deck covered with cork for maximum buoyancy, and a well ballasted keel.

In order to keep the line taut, a drogue anchor was towed behind the boat to

provide resistance to the pull of kites. Prior to this successful trip which was

made from Calais to Dover, several un-successful attempts were made from Dover,

all of which were met with adverse wind conditions.  These crossings resulted in many

public demonstrations of the invention and created positive publicity. During

this time Mrs. Cody also flew in her husbands man carrying kites to show her

confidence in his invention. All this had the desired effect and the military

finally became interested in his work with kites.

These crossings resulted in many

public demonstrations of the invention and created positive publicity. During

this time Mrs. Cody also flew in her husbands man carrying kites to show her

confidence in his invention. All this had the desired effect and the military

finally became interested in his work with kites.  “In October 1908 Cody had

been the first man to fly in Britain. In the five adventure filled years that

followed he had become what Vanity Fair magazine called ‘The British public’s

chief and best showman of flight’… On August 11, 1913 the British Army’s

headquarters at Aldershot witnessed a scene unprecedented even in its long and

valorous history…By early afternoon, according to the most reliable reckonings,

100,00 people had positioned themselves along the aspen lined lanes, from the

village of Ash Vale in Surrey to the Military Cemetery at Thorn Hill three miles

away…The procession was the largest the home of the British Military

establishment had ever seen…with the crowds standing two and three deep in many

places…His death had provoked an outpouring of spontaneous grief. ‘Millions who

had never seen him felt they had suffered a loss, almost as if they had lost a

friend’ wrote one who had known him…King George V had been among those to

express their grief …The King’s message captured the public mood, and added new

momentum to the campaign for Cody to be buried with full military honors. In the

immediate aftermath of his death, his family had begun arrangements for a small,

private funeral and internment at a local church. Within forty-eight hours,

General Haig and the War Office had offered Cody a plot within Thorn Hill, a

site ordinarily reserved for officers and holders of the military’s highest

honor. As far as anyone could ascertain, he was the first civilian to be granted

such an honor. He was certainly the first Wild West cowboy to be laid alongside

the heroes of Britain’s glorious military past.”

“In October 1908 Cody had

been the first man to fly in Britain. In the five adventure filled years that

followed he had become what Vanity Fair magazine called ‘The British public’s

chief and best showman of flight’… On August 11, 1913 the British Army’s

headquarters at Aldershot witnessed a scene unprecedented even in its long and

valorous history…By early afternoon, according to the most reliable reckonings,

100,00 people had positioned themselves along the aspen lined lanes, from the

village of Ash Vale in Surrey to the Military Cemetery at Thorn Hill three miles

away…The procession was the largest the home of the British Military

establishment had ever seen…with the crowds standing two and three deep in many

places…His death had provoked an outpouring of spontaneous grief. ‘Millions who

had never seen him felt they had suffered a loss, almost as if they had lost a

friend’ wrote one who had known him…King George V had been among those to

express their grief …The King’s message captured the public mood, and added new

momentum to the campaign for Cody to be buried with full military honors. In the

immediate aftermath of his death, his family had begun arrangements for a small,

private funeral and internment at a local church. Within forty-eight hours,

General Haig and the War Office had offered Cody a plot within Thorn Hill, a

site ordinarily reserved for officers and holders of the military’s highest

honor. As far as anyone could ascertain, he was the first civilian to be granted

such an honor. He was certainly the first Wild West cowboy to be laid alongside

the heroes of Britain’s glorious military past.”